We’re actively involved with town and shopping centre projects in all kinds of places; whether major premier city centres, or smaller local schemes in challenged less-affluent town centres. The solutions are invariably different and take time, but the processes often similar; requiring a holistic view to consider the unique characteristics and economic drivers of that location and what that means for demand for space and its typology going forwards. It’s about thinking outside the box and being brave to the possibilities. It’s about reimagining the real function of consumer ecosystems, which will often mean not thinking about retail places as retail only places.

More and more investors are looking to change income profiles from solely retail tenants to something much more resilient, sustainable, and with better potential for growth. This means creating a blend of different uses that meet the specific needs of that place.

There are swathes of town centres that need repurposing. Yet, the real issue is that the really challenged locations often have too many fragmented units that, firstly, can’t be converted economically and, secondly, are also no longer fit for purpose as retail. In some cases, the shopping centre is the town centre, so it’s not just a single asset or use that’s impacted by terminal decline. So, what should they be? One of the joys of my job is in digging into the fundamentals of a place and asking just that: who is it there to serve?

“Real estate is responsible for 40% of global emissions and for 40% of natural resource use. As of 2020, human-made materials exceed the total biomass of the natural world. Property development needs to be part of the solution not the problem.”

FUNCTION FINDING

Our role starts with place finding, well before we can consider place making. In many cases there was a functioning town centre with a multifaceted mix of uses prior to the arrival of the shopping centre. Rightsizing the retail provision is key but needs to be done tactically and strategically. We must focus on creating destination and experience, attracting more than just the shopper, and working with councils to create civic and community spaces.

Through our collaborative work with investors, universities and local authorities, we’re seeing a multitude of solutions. In Edinburgh,

the Ocean Terminal shopping centre is being repurposed with a new residential component; in Glasgow, the James McCune Smith Building is being reimagined as ahub for hybrid teaching, learning, community and study; and, in Aberdeen,the former BHS in being converted into a market with blended dining andevents space. Each case brings in new customers and stewardship for thatspace, which can have transformational benefits for the adjacent area.

However, while improving a place’s economic and social prospects isone objective, there’s an opportunity to kill two birds with one stonewhen we undertake redevelopment. Repurposing and repositioningprojects also provide a timely opportunity to go green.

DEVELOPING GREENER

Given the urgent need to reinvigorate towns, cities and shopping centres we have a responsibility: to build back better buildings that were never designed for more than one type of use, or to be run efficiently. We can’t afford to repeat the mistakes of the past. Retail places are the perfect places to undertake a number of environmental goals.

Today, most of the developments we’re involved in are planned with sustainability at their heart. Sustainable development can be an overstated but underutilised term, so what does it mean in this context?

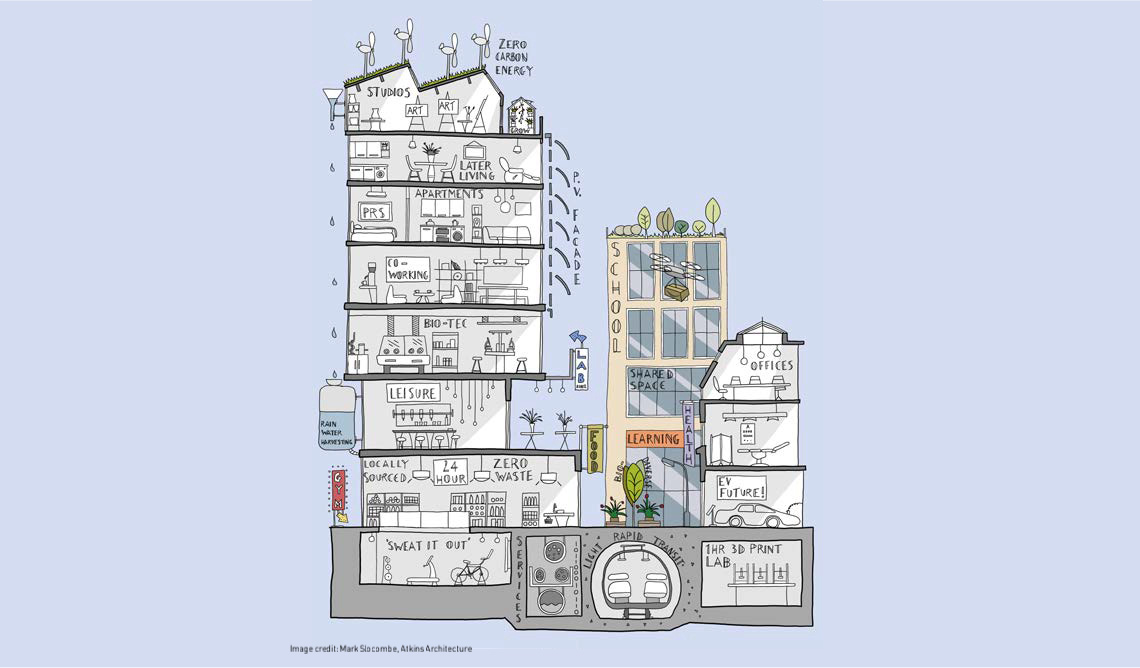

Green development of course needs buildings that are more efficiently built and operated. It also includes increasing natural light and ventilation. Perhaps even more importantly is creating spaces that are flexible and adaptable, so that if demands change the property doesn’t become redundant. Many shopping centres have created impediments to the flow of people in our city centres, what we often call ‘dead spaces’. Increasing provision of public, civic, and community-led spaces, improves connectivity and permeability.

Greener development means rethinking construction techniques or reusing what’s already there. It’s also about creating a more natural, immersive, integrated, and engaging environment. With sustainable development goals much like those often described within the principals of the Circular Economy or 15-minute neighbourhood; both elements may soon become part of planning policy in Scotland.

Greener development is also about greater biodiversity, which assists the environment but also has positive social, health, and wellbeing impacts. Let’s face it, consumers and communities prefer greener, cleaner spaces. So, if you want to make more sustainable and investable retail places and town centres, it makes economic sense to include environmental and social improvements to any repurposing or redevelopment project being undertaken.

Greener development means embracing technology that supports decarbonisation and consumer experiences. SWG3 Glasgow is a blended arts, leisure and community venue that utilises Bodyheat technology that transfers the heat from nightclub dancers to cool the venue on club nights and warm it in the winter. It’s a radical approach with a practical use, but it also provides an important educational and inspirational message on the scope of what’s possible.

A CALL FOR ACTION

Government policy on decarbonising properties is weighted towards the residential sector, while in commercial property the office sector has had the most notable transition towards a net-zero future; 45% of new office developments in London since 2018 have a BREEAM rating of Excellent or better. The lack of new development and the occupational challenges facing retail property in recent years means that the sector has so far lagged behind. That’s why Savills Reimagining Retail project is so important in bringing together stakeholders and experts from across the industry to consider the micro and macro challenges and how together we can address them.

The future of retail property matters because these places form the hearts of our communities. Whether they remain wholly retail or are diversified to provide a wider range of community amenities, economic drivers, leisure or health, it is in the adaptation of these places that will produce vibrant resilient places to lead us into the next century. As an industry, we have a once in a generation opportunity to do something more valuable and meaningful with them.

After all, what legacy do we want to leave? For me it would be knowing that this place is better because Savills was here. What excites me now is that green principles are no longer disconnected with the demands from development to drive economic and investment growth but are actually well aligned. The tipping point is not just that climate risk is on a cliff edge, or that society has finally come around to accepting the need to adapt, but that critically it’s the right thing to do economically. It is becoming increasingly clear that not doing so will impact on the ability to invest, or the returns from investment.

Develop with an environmental steer and you drive economic growth, but develop purely for economic growth could mean a missed opportunity when it comes to the path to net-zero, which we will only pay the price for sooner or later anyway. The cost of inaction will be a greater financial and environmental burden in the future.

Much of the greening of retail will be down to landlords improving their buildings and tenants cleaning up their supply chains. Yet the development world has a big part to play too in the adaptation of spaces that need to evolve, in bringing together multi-stakeholder centres, and in rethinking functions. In doing so, we’ll also create more meaningful, relevant places in the process.