Progressive retail landlords are now seeking to ensure that spaces are refurbished during lease breaks. This facilitates low carbon operations, by eliminating the use of fossil fuels in the base build mechanical services, and collaboration with tenants to ensure that fit out specifications prioritise the most efficient forms of lighting and equipment. During operation, landlords and tenants should be working together to set and achieve energy use intensity (EUI) targets, as 80% of building emissions can be attributed to occupier activities. These are focussed on energy use (rather than carbon emissions), and benchmarks can be obtained from the Better Buildings Partnership (BBP) and Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM). The CRREM EUI figures can also be used to define decarbonisation pathways, ensuring assets are compatible with the Paris climate agreement target of limiting global temperature increases to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius. The adoption of third party assessment methodologies, such as CRREM, avoids greenwashing and provides confidence that the buildings that are being let and occupied are compatible with national net zero targets.

Whose emissions are they anyway?

DEFINING AND TAKING OWNERSHIP OF THE PROBLEM

SCOPE 1, 2, 3

The world of emissions accounting is a confusing one. You may have heard of greenhouse gas emissions being split into three ‘Scopes’ for ease of organisational accountability. Emissions Scope 1 is fairly easy to define, as it relates to fossil fuels that are directly combusted by the organisation, such as petrol, diesel or gas. These would typically result from space or hot water heating in buildings or transporting products and materials. You can measure this from the gas meter or money spent on fuel. Emissions in Scope 2 are also relatively easy to define, as these result from the production of heat or electricity that’s consumed by an organisation, generally by lighting, ventilation, and computers in our buildings. Again, this is easy enough to measure from an electricity or heat meter.

Scope 3 is everything else and includes all other indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain; such as from goods produced by others, business travel, employee commuting, waste production, investments, and leased buildings. Because these emissions are those that result from a supply chain, an organisation is not in direct control and it’s a challenge to define a consistent boundary and therefore quantify these emissions.

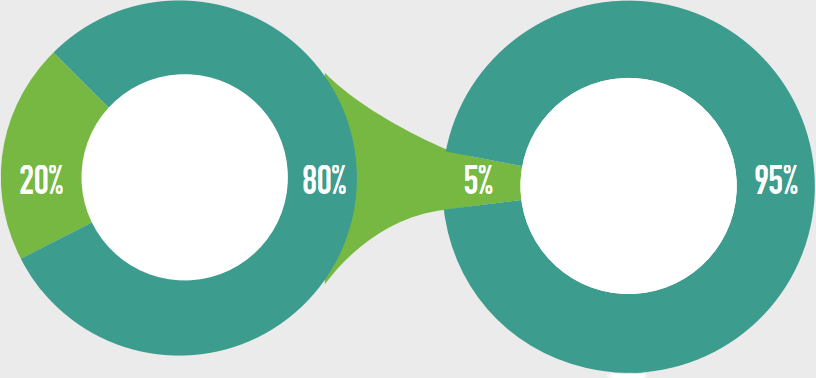

Scope 3 emissions can be a significant proportion of an organisation’s carbon footprint, with a considerable difference between a retail landlord’s Scope 3 emissions (related to the Scope 1 and 2 emissions of tenants) and that of a retail tenant (related to their supply chains). Landsec have suggested that 80-90% of their retail property emissions are Scope 3, and several retailers have indicated that ↑95% of their emissions are Scope 3.

IKEA’s 2019 Sustainability Report, for example, shows that only 3% of its total emissions fall within its retail and other direct operations.

WHOSE RESPONSIBILITY?

Retail landlords are increasingly working on reducing their Scope 3 through collaborating with their tenants. Due to the significance of their Scope 3, a retailer wishing to take responsibility for their emissions as part of a broader ESG strategy is likely to prioritise their supply chain to green their products and services, rather than the premises they occupy1. This can present landlords with a barrier to reducing their Scope 3, many of whom are seeking to install ‘green leases’2 to collaborate with occupiers to improving fit outs and operational energy usage.

Often retail tenants have resisted green leases because they are viewed as an additional commitment to costs that can’t be written off operationally and are seen to benefit their landlord’s investment values. Meanwhile, landlords that implement improved energyefficiency measures have spent the money, but they see the tenant as benefitting from reduced energy bills, hence why some landlords hold back on energy efficiency capex. This leaves us with somewhat of an impasse.

This mismatch in priorities neglects the fact that an occupier’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions, from the energy used to heat, cool, ventilate, and light their premises, will also be their landlord’s Scope 3 emissions, and that energy efficient refurbishment, fit out and operation can help to reduce these significantly. After all, it sends mixed messages to consumers if a retailer with high sustainability principles and sells eco-branded products, occupies poorly insulated buildings, with inefficient lighting, and leaves the doors open all through the winter.

A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH

Once greenhouse gas emissions from Scopes 1, 2 and 3 have been accounted for, an organisation should then be able to identify the largest sources of emissions and develop an overall decarbonisation pathway, possibly choosing to set organisational net zero targets within achievable timescales. Both tenants and landlords should commit appropriate resources to tackle the highest emissions sources first; prioritising resources to decarbonise different emissions sources over time, with relevant intermediate targets and measures set to ensure the organisation remains on track to achieving their net zero objectives.

The British Retail Consortium has developed a Climate Action Roadmap3 to provide retailers with detailed guidance on decarbonisation pathways, with a net zero plan in place for shops and warehouses by 2030. This will be encouraging for landlords as it suggests that increasingly tenants are willing to engage in making the necessary improvements to how they fit out and maintain their shops.

While landlords have little control over a retailer’s upstream supply chain emissions, they may be able to influence their downstream emissions, which include customer facing initiatives, providing sustainable living information, facilitating low-carbon travel, and improving product end-of-life recycling.

A MATTER OF PERSPECTIVE

While Scope 3 for landlord and tenant differ significantly, with different challenges to resolve, there is a growing train of thought that with the increasing importance of ESG principles to both investors and consumers, a landlord should seek improvements in the ESG credentials of their tenants. So, should landlords take an increasing interest in their tenants’ Scope 3? There is good reason to think that there will come a point when the social, ethical and environmental conduct of retailers will impact on the ESG credentials of their landlords, which could become a problem for funding or valuation down the line.

If this happens then this may include some landlords reducing exposure to retail tenants deemed to have the worst Scope 3 performance. However, few landlords have the luxury at present to be too choosy about who they lease space to.

“We should aim to account for carbon in the same way we do with finance, with an organisation’s greenhouse gas emissions forming another column on the balance sheet”

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Quantifying all Scope 3 emissions is no mean feat and there will always be a degree of double counting, where a supplier’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions are the retailer’s Scope 3. Due to the difficulty in obtaining reliable figures for Scope 3, many organisations make commitments to achieve net zero for Scopes 1 and 2 by an earlier date than a Scope 3 net zero commitment, giving them time to work with supply chains to better understand and reduce emissions. Just because data might not exist today, it doesn’t mean it won’t tomorrow, and those supply chains that are able to provide data upstream will be seen as more proactive than those that aren’t.

PRIORITISING ACTIONS FOR RETAILERS:

- Investigate the energy efficiency of potential spaces for occupation

- Set relevant EUI targets in line with CRREM guidance

- Work with landlords to monitor, track and improve operational energy performance

- Seek to procure renewable energy where possible

- Request data from supply chains to define Scope 3 emissions

- Monitor, track, report and celebrate progress to decarbonisation

PRIORITISING ACTIONS FOR LANDLORDS:

- Develop processes to record operational energy use from tenant spaces

- Work with tenants to monitor, track and improve operational energy performance

- Use lease breaks to undertake sustainable retrofit and decarbonise building services

- Monitor, track, report and celebrate progress to decarbonisation

Eventually, we should aim to account for carbon in the same way we do with finance, with an organisation’s greenhouse gas emissions forming another column on the balance sheet, so landlords, retailers and consumers are able to understand the true carbon cost of their purchasing and investment decisions.

LANDLORD EMISSIONS

RETAILER EMISSIONS