WHAT IMPLICATIONS DO EPCS HAVE ON RETAIL’S RESPONSE TO THE CARBON CHALLENGE?

WHY ARE EPCS IMPORTANT?

British shops currently emit over 8MtCO2 (million tons per annum) more than new build standards. The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) provide legislation and timescales of how leased buildings need to improve their energy efficiency in the coming years, via their Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs). EPC gradings range from A-G and are the same system we’re familiar with when buying a fridge, with G being the worst performing. In order to optimise a building’s efficiency there are severe consequences for a landlord who fails to climb the EPC ladder. Properties that fail to meet the MEES Standards can no longer be leased and could become ‘stranded assets’.

As from April 2023 it will not be permissible to continue to rent commercial buildings with an EPC of Grade F or G. Furthermore, the Energy White Paper 2020 confirmed the Government’s intention that all commercial rental buildings must be EPC Grade B before April 2030 (with an interim step to grade C in 2027). These regulations refer to England & Wales, with Scotland bringing regulations through earlier. However, to simplify matters in this discussion we group all UK stock together because the underlying message remains the same.

A substantial proportion and quantum of UK retail real estate needs to improve its EPC grade before the end of the decade, something that will challenge the commercial property market and regulators alike in the coming years. The benefit is that this would reduce our national emissions by 5.4MtCO2 per annum.

SO WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS AND HOW MUCH RETAIL IS AFFECTED?

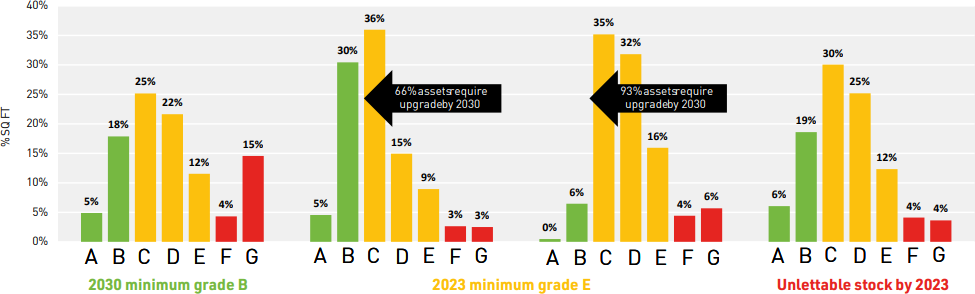

By 2023, 185,000 million sqft of EPC F&G grade retail space is at risk of being unlettable unless urgently improved.

By 2030, 1.4 billion sqft of retail space needs to reach EPC grade B; equivalent to 83% of all UK retail real estate.

This global figure is quite worrying and a lot for any of us to get our heads around. There are significant differences in how these ratings vary across different asset classes, unit sizes, geographies, and different parts of our town and city centres. However, no sub-sector is clear of the challenge. Questions remain about how implementable the legislation is given the scale and cost involved.

RETAIL ASSETS DIFFER IN PERFORMANCE

For landlords with a significant exposure to retail property the EPC cliff edge can be seen as an insurmountable challenge. On the one hand, they are increasingly led by ESG drivers that invariably align them with the need to reduce property emissions. On the other it can be difficult to know where to start given wider environmental concerns across large estates. Properties could be modified in incremental steps, which may be more expensive in the long run as well as more disruptive to tenancy, or upgraded in one go at a greater upfront cost and with the possibility that the technology available will be quickly surpassed.

Looking at the main retail asset classes of shopping centres, retail parks, and supermarkets (i.e. stripping out high streets etc), these core retail assets account for 1.1 MtCO2 pa compared to ‘new build’ standards. It’s worth noting that this is not even reaching a net-zero position.

Of these asset types, by 2023, 35m sqft can no longer be leased unless improved above F&G grade and by 2030, 335m sqft will have needed to be improved to grade B. Critically, 4m sqft retail parks and 12million sqft shopping centres could be ‘unlettable’ within the next 12 months.

Put another way, 80% of institutional retail stock needs improving by 2030 – 8% before 2023. However, a considerable number are already heading towards the 2030 goal, with 20% of the total floor area already at Grade A or B.

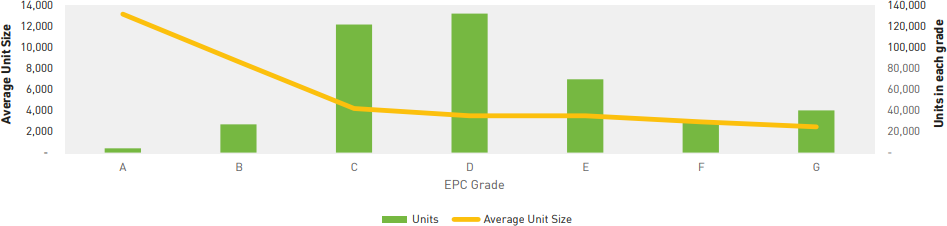

There are different degrees of exposure to the regulations. Retail parks are the sub-sector most advanced towards reaching Grade B for 2030 (35%) and a further 36% at Grade C. The unit size and configuration is generally seen as being easier to retrofit improvements on a cost per sqft basis, although the large floor areas do require considerable heating and cooling. This sector also has the fewest poor performing assets.

While two thirds of retail park assets don’t currently meet the 2030 target, that’s far less than shopping centres where 94% of the space will need to be addressed across all EPC bands.

Supermarket units also appear to be performing relatively well, with 25% already at a B standard and just 8% at risk of 2023 stranding. However, refrigeration is a significant problem and one that is not measured by EPCs, which is why many in the industry consider an ‘actual usage’ certification (e.g. NABERS) more useful than the current MEES regulation in addressing a unit’s emissions.