The trends point to repurposing, but retail should remain at the heart

This year has brought about monumental changes to the retail landscape. Many trends that were creeping into effect pre-Covid have been forced to mature almost imminently this year, posing a number of questions over the structure of the retail market as we know it. How many of these trends will reverse after the pandemic, what has been accelerated and what has changed beyond recognition?

Ecommerce

The domination of ecommerce has been the talk of the town this year.

Is it fully justified?

The rise in internet retailing has been at the forefront of retail evolution for a number of years and at the end of 2019 accounted for 19% of retail spend in the UK. Online sales spiked during Lockdown#1, briefly accounting for a third of all UK retail sales. However, this has since softened and, once lockdown measures have eased, is forecast to settle at between pre-Covid and peak lockdown levels, with a penetration rate of around 23.2% likely by the end of 2021, according to GlobalData (figure 1); more than five years earlier than previously anticipated and yet not an irreversible trend in shopping as has previously been reported in the press.

The remaining three-quarters of retail sales will still be accounted for through physical stores, emphasizing the ongoing pivotal role of bricks and mortar. The importance of omnichannel retail has become vital for the existence of many retailers, with efforts to improve or introduce Click & Collect accelerating this year, somewhat reinforcing the need for an element of physical presence.

Online supermarket sales, which prior to the pandemic lagged behind non-food, has been particularly affected; almost doubling in 2020 from 7% to 13%. However, CACI report that the highest online grocery penetration is in locations with a strong store presence, so there remains synergy between online and offline.

So the question perhaps isn’t whether physical retail is necessary or not, but more how much is needed, with ‘rightsizing’ becoming a feature of most retail-related agendas.

Figure 1: Online sales as a proportion of all retail sales

Source: Savills Research; ONS, GlobalData

The Doughnut Effect

Footfall and mobility data have been useful benchmarks for understanding the shift in consumer demand caused by the pandemic. Following the initial reopening of retail and leisure after Lockdown#1, commuter and market towns in the UK experienced a more robust recovery compared to city centre workplace and destination locations. The Local Data Company (LDC) noted that year-on-year footfall across a sample of residential locations averaged -43.1% per week between March and August, compared to -67.7% for office-based locations.

This echoes data reported by Google regarding mobility across outer-city retail locations compared to city centres. For major cities like London, this has created a ‘doughnut effect’ whereby outer-London boroughs have seen far quicker recovery levels, effectively reinforcing the importance of local amenities and demand for nearby retail.

Similarly towns across the UK, including those normally impacted by strong regional shopping or city centre competition, are seeing greater resilience and increased loyalty as people increase the time spent in the areas they live through altered working patterns and the need to decrease the contact time with retail favouring convenience formats.

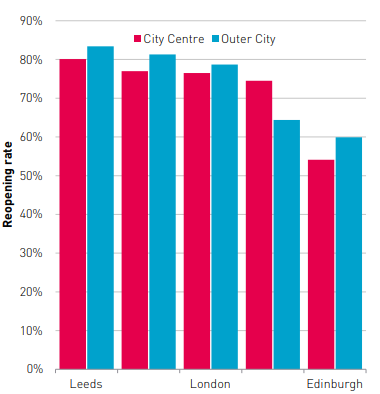

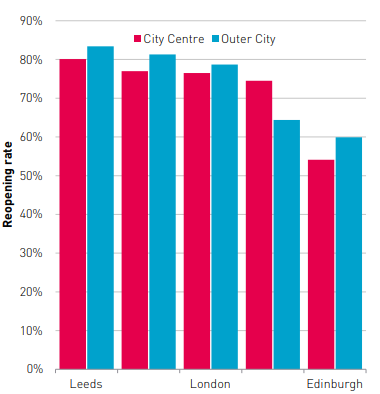

Furthermore, LDC has demonstrated the reopening rates of retailers and businesses across outer city locations have recovered more quickly when compared to city centres (Figure 2 & 3 below).

Figure 2: Reopening rate -city centres vs outer city locations

Source: Savills Research; VisitBritain

Work-life Balance

Arguably, the most significant cultural movement in 2020 has been the forced change to homeworking and the likely impact this will have on city centre office and retail markets. There appear to be diverging attitudes amongst workers on whether jobs can be performed as well remotely and it is becoming clear that it depends on the type of role and the individual’s personal circumstances and preferences. For some the workplace is a hub for creativity, collaboration, learning and social activities, for others the video call allows for all of these, and for those who have endured years of commuting, homeworking can provide an improved work-life balance. The long term outcome for most is likely to be a blended approach.

Figure 3: Reopening rate -city centres vs outer city locations

Source: Local Data Company

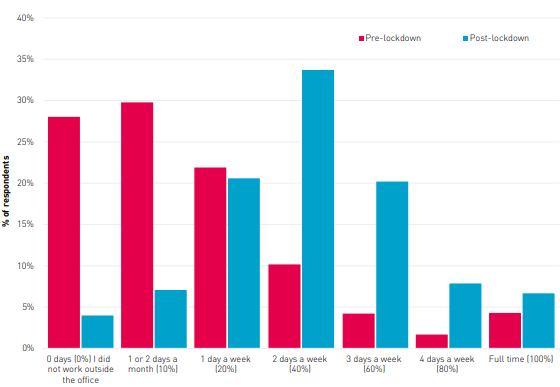

Savills Office FiT survey has found how attitudes to homeworking have changed dramatically since March 2020. Pre-Covid less than 20% of office workers had the preference to work at home more than 1 day a week. Following the onset of the pandemic over 80% want to work at home more than 2 days a week (figure 4).

This could fundamentally change the way our towns and cities will function in the future. CACI estimate that 25% of retail spend in city centres is from workers and 40% in London. Even a 10% shift in behaviour would significantly alter the need for retail space in these locations, but by the same token, increase the need for space where people live.

Figure 4: Pre- & post-lockdown remote working preference

Source: Savills FiT

40%

Central London Spend from Workers

25%

City Centre Spend from Workers

Source: CACI

Purpose-driven shopping

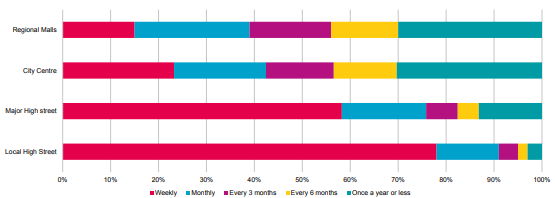

Another key theme to mature this year is the importance of convenience and purpose-driven shopping; a trend that has supported resilience across retail parks, supermarket anchored schemes and smaller high streets over shopping centres and major city centre retail. We have long advocated the importance of community retailing, having tracked the ongoing polarisation between destination and convenience based trips that has prevailed over the last decade. Convenience trips are typically local, frequent, essential and functional, whereas destination trips more experiential, indulgent and leisure based.

Most convenience based trips are made in combination with another journey, or are located close to a place of residence. The longer workplace displacement and social distancing persists, it is reasonable to assume that this trend will continue long after the Covid crisis.

So where does this leave destination retail? Not withstanding there being significant challenges ahead, there remains an important place for prime retail and leisure destinations in the long term. Some things, experiences in particular, cannot be delivered online and convenience based places lack the infrastructure. However, it is also reasonable to surmise that mass vaccination needs to be in place before we can put this crisis behind us and return to normal, or at least move to the next normal. Either way, there is little doubt that there will be a major structural change that will see these places need to reduce the floorspace they currently occupy, even if the retail and leisure users remain at their heart.

Figure 5: Visitation Frequency

Source: Savills; PlaceDashboard; Ellandi

Retail Vacancy

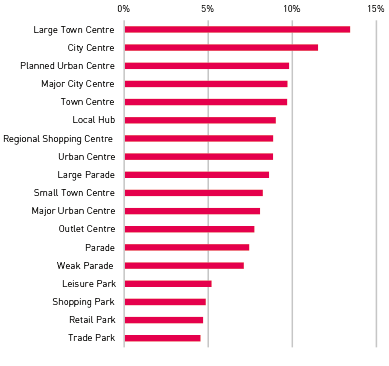

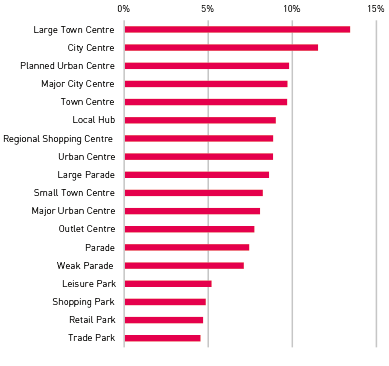

The declining need for space is by no means a new phenomenon; the number of retail outlets has been falling for decades. The Local Data Company announced that store closures in H1 2020 increased by 21% year-on-year, resulting in a net loss of 7,834 stores. While this trend is set to continue, not all retail places are affected equally.

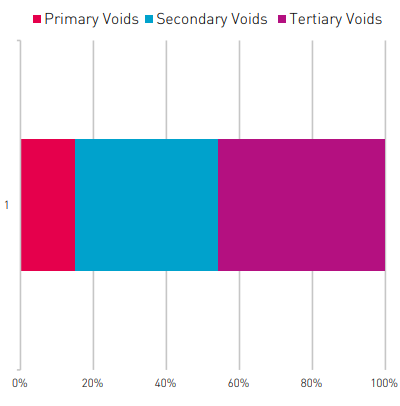

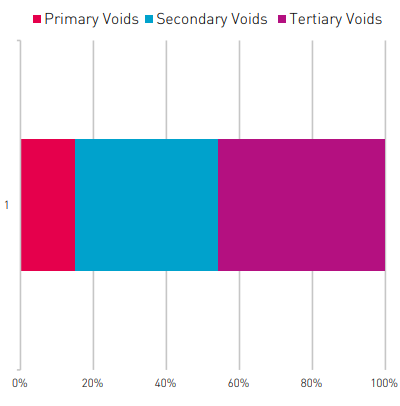

The UK currently has 142 million sqft of vacant retail space, equivalent to 12.6% of retail units. But vacancy within any centre is rarely uniform (figure 6a). Examining different retail pitches within town and city centres nationally shows that vacancy increases outside of the retail core, with 46% of empty units being within the tertiary retail pitch, compared to 15% in the primary retail pitch (figure 6b). This demonstrates how retail provision has shrunk or moved within high streets, causing marginalisation and more limited occupation at the periphery.

Figure 6a: % Unit Vacancy Rate by Retail Place Type

Source: Savills Research; LDC; GOAD; Geolytix

The void rate itself masks a more serious concern, void length. Even in the most successful retail places there is an increasing proportion of vacant units that are empty for long periods or even permanently, with 40% of vacant units having been empty for 3 or more years. This problem is exacerbated in most towns and cities across the country and accounts for 60 million sqft, most of which is no longer needed.

Figure 6b: Distribution of Vacant Units by Retail Pitch

Source: Savills Research; LDC; GOAD; Geolytix

Furthermore, with changing consumer trends we estimate that by the end of the decade almost 308 million sqft of retail space will be redundant, increasing to 492 million by 2040. It’s not that these places don’t function as retail spaces, they simply have too much of it. This problem has been creeping up on us for a long time and Covid or not, is reaching a critical moment in which we need a radical change in thinking of all retail places and town centres.

Nonetheless, there remains demand for new retail concepts that fit with evolved consumer preferences, with the opportunity for repurposing redundant retail to breathe life back into town centres which, post-Covid, has become more important than ever before.