Rebuild or retrofit:

the financial case

IS IT CHEAPER TO REDEVELOP, OR ARE THE ECONOMICS MOVING IN FAVOUR OF REUSE?

RETAIL SPACE NEEDS TO ADAPT

It’s a question that faces all investor landlords with aging stock: whether to replace or refurb it. It’s a fundamental economic dilemma as much as a moral one, but prior to the ESG agenda becoming central to real estate decisionmaking, the economics would invariably win. However, a sea of change is now seeing economic and environment priorities becoming more aligned, which means that landlords may start to have more options when it comes to the future of their retail assets. But is it just about the ‘bang for buck’?

To repurpose, reposition or improve defunct retail space, it has often been the case that it is more financially rewarding to redevelop a site than adapt it. Retailer’s space requirements and consumer demand, particularly in shopping centres, have evolved several times in the last few decades; quickly dating some relatively young schemes and highlighting their inflexibility for adaptation.

Even recently, when retail repurposing has become a hot topic due to significant occupational headwinds in some quarters, rebuilding has often been seen as more viable because redeveloped schemes are able to seek value from expansion and densification. Retrofitting on the other hand, can require significant compromises due to the existing building configuration and structure that tinkering with can, at times, feel like driving a square peg into a round hole.

However, this is not always the case. Retail park and larger shopping centre units tend to lend themselves well to adaptation, whether to fit out the needs of a new tenant, or to upgrade environmental performance. Small high street units are however, an entirely different proposition.

So, how does refurbing or rebuilding within the retail sector work in practice?

TO REBUILD, OR NOT TO REBUILD…

From our experience, any new building stock in the retail market is high performing from a sustainability perspective; although the embodied carbon remains considerable. But, how many brand new-build retail schemes are actually being constructed? In the UK, the number of new significant retail schemes in the last decade can almost be counted on one hand.

Instead, most retail development is happening to existing schemes. Repurposing redundant retail stock is starting to gather pace, with different places seeing units reconfigured or wholesale demolished and rebuilt. Department stores have typically lent themselves well to the former—though layout is often a challenge— while shopping centres or high street blocks are likely to see more significant redevelopment and, often, with a higher density of uses when complete. But these schemes all have one thing in common: scale.

For large sites, rebuilding usually wins out because of the opportunity to create something more intune with modern requirements, allowing a more radical change in design and use, and increasing the overall footprint. It’s no coincidence that some of the retail conversions we’ve seen come out of the ground most quickly have added further floors on top to make the redevelopment stack up financially.

When building a new unit from scratch the building can

be meticulously designed to accommodate renewable energy, operate efficiently and still meet the needs of the tenants and perhaps commanding higher rents because the overall package is significantly better than what came before it.

On the other hand, taking the decision to knock down and rebuild is not only a moral dilemma but one that the industry is waking up to because of embodied carbon. The main materials for new developments (steel and concrete) generates a lot of embodied carbon, with concrete alone causing eight per cent of global emissions; approximately half of the whole-life emissions of a building could come from the carbon emitted during the construction and demolition.

ESG, while a key motivator in the debate, isn’t the only factor however. The financials involved in construction have begun to swing the economics away from redevelopment, with labour costs, shortages, and, particularly, the cost of materials proving major concerns. Early 2022 saw timber almost double the cost in 2015, while steel and concrete were up 80% and 40% respectively over the same period. This means that the build costs are moving more in favour of retrofitting.

CHALLENGES TO RETROFIT

Reusing buildings does have several economic benefits, such as no demolition costs, a quicker programme, and less time through planning. Environmental benefits include extending the buildings life and reducing its embodied carbon and, while there may currently be limitations on what can be done from a sustainability perspective, in terms of unit fitouts and operational carbon, technology is rapidly evolving to create more efficient and more recyclable materials.

However, according to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), 11% of UK construction is on fitouts and buildings may have 30-40 fitouts during their lifetime. That’s a lot of material to throw away and perhaps it’s the lack of adaptability of space that requires such drastic alterations. Either way, landlords have traditionally—and perhaps casually—undertaken refurbs as often as necessary to secure tenants. The ESG agenda is rapidly putting these issues into the spotlight. And, of course, if you reduce the number of fitouts you reduce the overall cost of future capex.

There’s no getting away from the fact that some improvements are incredibly challenging without making major costly structural adaptations. As a prime example of the difficulties faced, we’ve recently advised on photovoltaic (PV) installations on out-of-town retail parks. When retrofitting PV panels onto existing stock there are a number of variables: can the frame take the load, does the orientation of the building generate sufficient power, and, significantly, who pays for this and who gets the direct benefit?

It’s still the case that the landlord usually pays for the design and installation of renewable energy sources such as PV panels, yet tenants also see the benefit. If you couple this with the tenant wanting the landlord to maintain the system and for the premises to become Internal Only Leases there’s an impact to ownership costs and investment. Landlords may see this as a no-win scenario. When you factor in that the majority of out-of-town retail parks are held by large landlords who group sites together in portfolios, unless there’s a site-wide campaign, one unit alone will not allow the portfolio to be classed as green.

ESG VERSUS CAPEX

This question is increasingly being decided by one big factor: the climate crisis. Before any financial case can be understood, investors should first be appraising their retail standing assets against their ESG strategy—if they have one—and, as a minimum, against the UK Government’s Net Zero Carbon strategy to eliminate emissions by 2050.

This can be done by undertaking an ESG due diligence appraisal of a retail building or portfolio to help understand the current ESG verses the potential performance (i.e. the ability to influence).

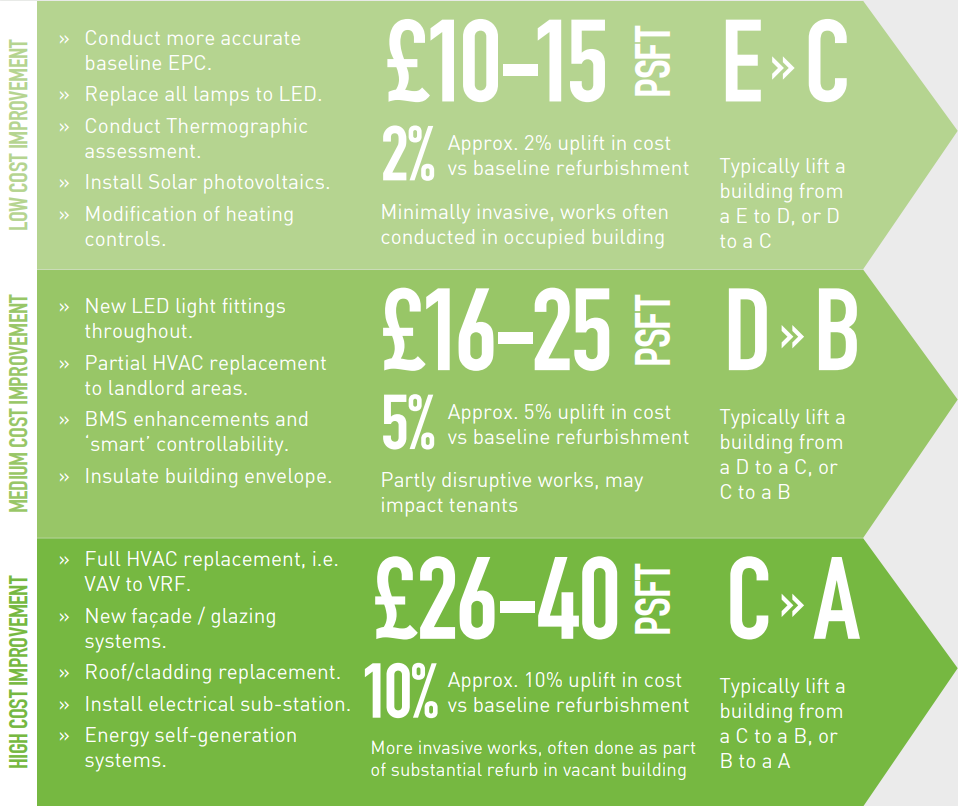

The EPC challenge faced by landlords is also a considerable headache if they’re to reach MEES grade B by 2030. We estimate that the cost to upgrade a retail shell from an E to a B is likely to be around £40-80 sqft (figure 1). This is a significant challenge for landlords with huge estates and the capex is massive, but equally for owners of small shops (where, in fact, a larger proportion of ‘problem’ stock lies) this presents an almost impossible proposition.

EPCs are, in many ways, an unwelcome distraction from other more beneficial ways of addressing the problem. Other aspects to consider are energy in-use and carbon emissions, energy source, and climate change exposure. The focus here is understanding the operational carbon emission as a metric. Once this is understood, it can be modelled using tools such as the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) to determine the carbon emissions relative to its stranding risk—that is, the chance of a building becoming untenable and, therefore, devalued on the net zero carbon pathway to 2050.

The most convenient times to address issues of operational carbon will usually be at lease end, plant replacement cycles, or other planned refurbishment works. However, the key consideration in identifying the optimal time to make these interventions by balancing cost, access, technology advances, and the decarbonisation targets with the excess emissions released in the interim period.

Furthermore, a poor-performing building doesn’t necessarily mean knock it down and build new. The next steps are to look at what can be done to influence the building verses the embodied carbon impact of redevelopment. With this in mind, instead of just comparing the £/sq ft between new build and retrofitting a development when undertaking a viability assessment, investors really need to start considering Whole Life Carbon as part of the viability. It won’t be long before the government wakes up to embodied carbon legislation and what the industry is already doing itself.

GREEN SHOOTS

Encouragingly, we see many responsible landlords improving their sites, shared areas, and demise under their control by investing heavily in sustainable measures. Electric charging points, LED lights, and removing gas are becoming standard for many. As a sector, retail landlords and retailers are already heading in the right direction. Common parts of retail parks and shopping centres are greener than ever, but there’s still a long way to go.

Tenant fitouts, too, are increasingly efficient. We’re seeing clauses in leases and agreements stating the premises must meet certain standards. Retailers know consumers want to see green credentials. But, in the same way that landlords can’t simply fund green incentives on the tenants’ units, retailers are unlikely to commit funds to install complex systems into a unit they don’t own. Why would a retailer introduce a risk and maintenance factor to their premises for the landlord to get the benefit? There’ll be a monumental move to improve premises going forward and when a tenant is taking a long lease there’s more incentive for both parties to invest as everyone shares in the benefit.

Ultimately, there’s no straightforward answer whether to demolish and rebuild or retrofit. The financial case, therefore, should be predicated on the ESG Strategy. In many cases, the more environmentally-friendly option is to retrofit a building using materials that are as sustainable as possible, while at the same time maximising its energy efficiency. However, it’s difficult to bring an older building up to the levels of efficiency that are possible using cutting-edge technology in a new build.

Furthermore, it’s far from clear how the industry will improve the ‘forgotten stock’—the 75% of UK retail real estate that isn’t owned by large institutional investors—is under multiple ownership, is often underinvested, and lacks both the capital and information required to make greener decisions.