HOW ARE GOVERNMENTS AND BUSINESSES TACKLING RETAIL PROPERTY EMISSIONS ACROSS EUROPE?

THE GREEN DEAL

Many doubts and questions come to mind when speaking about ESG to landlords. The topic is often either viewed at best as a mere jackpot solution to retrieve financial benefits from, or at worst as a burdensome encumbrance to deal with. Across several countries, we observe that the retail sector is slower to move towards ESG compliance than other asset classes.

The core message appears to be a so far limited response that tends to be geared mostly to corporate investors operating cross-border, who are directed by their own ESG agendas rather than policy. There is a clear disconnect between public and private stakeholders, which urgently needs to be brought together where objectives lack linearity. Added to this is confusion arising from the multitude of stand-alone initiatives as well as the complexity and fragmentation of the asset class itself.

So, what are governments and businesses doing to forward the agenda?

In accordance with its commitments under the Paris Agreement on climate change, the EU’s goal is to be carbon neutral by 2050. To achieve this goal the EU Commission has set out a broad range of ambitious policy measures under the European Green Deal: the agreement that bound member states in transforming the EU into a sustainable and climate neutral economy. At the core of these measures sits the Commission’s strategy on sustainable finance which aims at mobilizing and redirecting private investments towards ‘green’ economic activities.

The EU Taxonomy is a tool, or better yet, a classification system, with the aim of helping EU investors redirect and increment sustainable investment while respecting the European Green Deal. The Taxonomy pinpoints performance thresholds for economic activities that bring substantive contribution to the environmental objectives set therein, do no significant harm (DNSH) and meet the minimum safeguards.

Essentially, it outlines the method to identify sustainable economic activities that are in line with six main objectives: climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, sustainable use of and protection of water and marine resources, transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems. Although generic, the principles represent the basis for the standardisation of best practices in influencing investment flows towards sustainable activities.

EU TAXONOMY IN PRACTICE

With a multitude of ESG initiatives on the one hand and the current lack of reliable long-term goals at both European and national level on the other, there is a sense of widespread confusion among landlords and investors. In an effort to push the agenda, individual solutions are created, external service providers are used, and numerous sustainability declarations are signed. Nevertheless, it can be observed that many of the scoring models, benchmarks or other valuation methods that have been developed on the market or by the companies themselves are only a momentary snapshot; a common market standard is missing. However, there are no tools to manage the properties during operation that are specifically designed for facility and property management. We should also be mindful that some environmental performance certifications, such as GRESB, are there to provide an international standard of ESG performance but may not themselves be aligned with carbon reduction targets (unlike CRREM, which is). Therefore, unless operating at net-zero, even the best performing properties by most certification benchmarks are likely to have a significant need for optimisation by 2050 in order to meet the Paris climate targets (figure 1).

Interpretation across borders might vary. Generally speaking, a distinction should be made between existing assets and developments. Increasingly we’re seeing investors seeking to maximise an asset’s value by considering both adjustment works and improvements through retrofitting. These works entail CapEx estimations which are typically aimed at the potential obtainment of green and social certifications such as LEED, BREEAM or WELL. In Germany, the German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB) has just created a special certificate that checks ESG verification along the taxonomy.

Meanwhile, Italian-based management companies tend to have an approach towards ESG issues in real estate based on their resonance. For example, companies that benefit from international markets and are globally present are generally more likely to include issues that are deeply connected with ESG matters in their strategy and/or corporate social responsibilities. Conversely, management companies that operate mostly within Italian borders have a tendency to underestimate, or at most delegate, ESG-compliance issues to external specialists.

LANDLORD PROACTIVITY

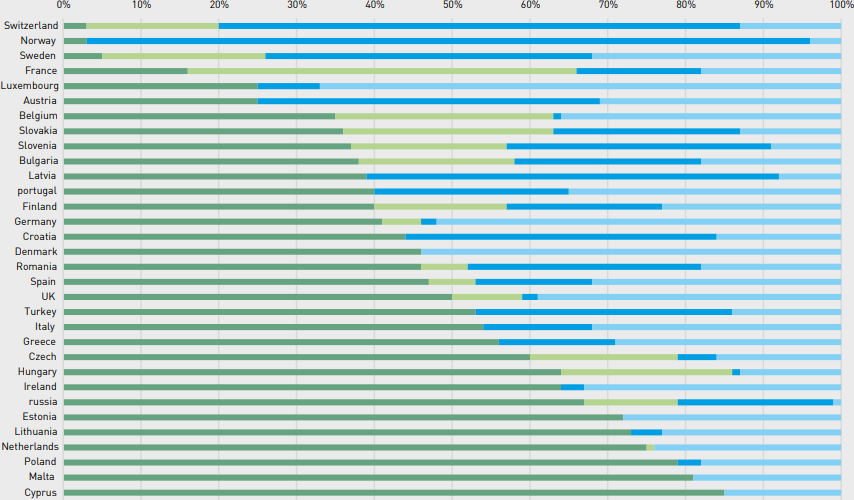

One of the challenges of a cross-border approach to sustainability is the different priorities, issues and infrastructures already in place in different territories. Consider, for example, how electricity production differs across Europe (figure 2). Switzerland and Norway generate over 95% of their electricity from renewables or hydro, so there may be limited benefit to a mass rollout of PV on shopping centre roofs, compared to Malta and Cyprus where the climate is both considerably sunnier and fossil fuels still account for more than 80% of electricity generation. This is just one reason the taxonomy is a guide rather than policy and it is anticipated that individual countries will interpret and legislate accordingly. However, with this comes the risk of a lack of urgency and alignment.

In addition, there are numerous site- and owner-specific peculiarities. In the Netherlands, there are fewer large-scale shopping centres than many other European markets and the majority of the stock of retail real estate is located in inner city areas. These areas contain a high share of older properties that are less sustainable and more difficult to retrofit. Furthermore, ownership is highly fragmented, and for private investors especially, incentives for improving the sustainability of the properties seem to lack.

There are not only different approaches across the different countries, but even within the asset class, individual solutions are required. For instance, the challenges of a shopping centre are not the same as those of a discount supermarket. There are certainly overarching measures that can be implemented in all properties, such as the use of LED lighting or the generally increased electrification of buildings, but each retail type is confronted with its specific requirements. For instance, the inclusion of the social factor is of greater importance in shopping centres than in other retail properties.